The Man Behind the Man Inside the Turret

There are many books and articles that have been written about strategy, combat and combat operations. The infantry, small arms, tanks, artillery, aircraft all get their fair share of coverage by authors, either as part of the wider story of combat operations, or as studies in the ‘minutia’ of what makes the equipment ‘tick’. What has perhaps not been emphasised enough is what makes all this equipment keep ‘ticking’.

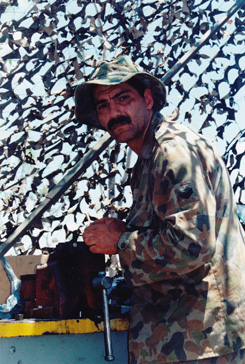

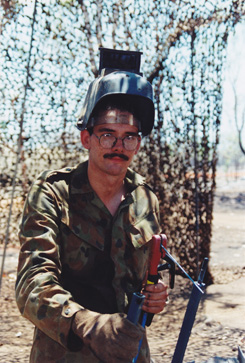

Behind every ‘tankie’ or ‘bucket’, driver, medic, or ‘grunt’ ….in fact every service person in the Australian Army and every piece of equipment that they operate in war or peace, is another, often unheralded group of service personnel. Without them, and their expertise, everything — literally — would eventually grind to a halt: stop firing… stop moving … stop … functioning.

While every ‘part’ of the Army ‘whole’ must play its role in ensuring the Army is able to carry out the tasks set for it by Government, the Corps of Royal Australian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers is the part that keeps all the Army’s equipment operating. They are very much the ‘you bend it … we mend it’ (the polite version of ‘you f**k it … we fix it!) arm of the Australian Army.

The decision to form the Corps was based upon the formation in the British Army of the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers (REME). The Royal Warrant authorizing the establishment of the new Corps of REME was issued on 22 May 1942. Based upon this precedent, the decision to form a similar Corps in the Australian Military Forces was announced in General Routine Orders on 16 October 1942, and the Corps of Australian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers (AEME) came into existence on 1 December 1942.

The formation of the new Corps was covered in detail in the Master General of the Ordnance Equipment Memorandum Issue 2 of January 1943. In short, the Corps was formed by absorbing the entire Mechanical Engineering Branch of the Australian Army Ordnance Corps, with appropriate changes to unit designations and appointments. In addition, most tradesmen involved in maintenance and repair of equipment in units of other Corps were transferred to the new Corps in a several phases.

There were, in those days, some exceptions. First and second echelon repairs of Service Corps vehicles, and first echelon repairs of signals and engineering equipment, were still carried out by maintenance sections and workshops of the Corps concerned, but overall, the more complex maintenance and repair of the Army’s equipment became the responsibility of AEME. This would eventually be rationalized such that the majority of repairs and maintenance would be handled by AEME.

Indeed, the January 1943 description of the Corps’ responsibilities and the level of its importance to the Army as a whole were described as being ‘analogous to that of the AAMC [Australian Army Medical Corps]. Its responsibilities regarding the maintenance and repair of mechanical vehicles and equipment are parallel to those of the AAMC regarding the care and treatment of personnel: its LADs [Light Aid Detachments] and workshop units have their counterparts in the RAP [Regimental Aid Post], CCS’s [Casualty Clearing Stations] and hospitals of the AAMC; considerable numbers of the personnel of both Corps serve on attachment to units of other Arms or Services, and the officers of both Corps are, in the main, qualified by their civil professional training for their military duties.’ The special requirement that personnel were qualified engineering tradesmen was recognized in their designations: not a ‘Private’, but a ‘Craftsman’, not a ‘Sergeant Major’ but an ‘Artificer Sergeant Major’, and so on.

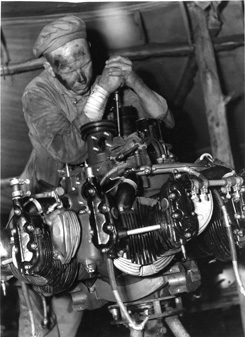

The broad responsibilities of the new Corps were defined as ‘keeping in as high a state of repair as possible, all vehicles, arms, armaments, instruments and other technical equipment used by the Army, and with the recovery and repair of equipment which is damaged or becomes defective.’ Thus there were two broad areas defined for the Corps from the outset: the first being the overall maintenance of the Army’s equipment, including the instigation of functional improvements. Units and individuals were still responsible for carrying out preventative maintenance, with the new Corps’ role defined as being ‘additional and complimentary’ to it.

The second broad area was recovery and repair of equipment to make it ‘battleworthy’ again. Physical breakdown while on operations or damage by the enemy could quickly whittle away a unit’s ability to carry out their function, no matter how well their equipment had been maintained previously. It was the new Corps’ responsibility to retrieve the equipment from wherever it lay and carry out repairs pragmatically in order to make it available as soon as required. In desparate times, such repairs may be just enough to make the equipment functional again, rather than involving more detailed and time consuming repairs for long term operability. Thus, the Corps’ role was – and is – to be highly responsive to the operational commander’s needs in battle.

Not that this meant working in the confines and relative safety of a rear base or depot: far from it. At the time of its formation, AEME was defined as a ‘combatant Corps, and enjoys all the privileges and responsibilities that this status implies. Its combatancy is actual as well as technical, and upon AEME personnel devolves the responsibility of defending its workshops and installations against enemy attack’. Indeed, the combat aspect of the Corps’ work has reached considerably further forward into the combat zone than defence of their own installations.

On 10 November 1948, His Majesty King George VI granted the title ‘Royal’ to several Corps of the Australian Army, including AEME. The publication of Australian Army Order 99 of 31 December 1948, under the heading ‘Grant of the Title ‘Royal’ to Certain Corps of the Australian Military Forces’, stated that ‘in recognition of their services during World War 2, His Majesty the King has given approval to the granting of the title ‘Royal’ to the under-mentioned Corps of the Australian Military Forces, whose designations will, in future be as follows: The Royal Corps of Australian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers…’. The title was later revised to the Corps of Royal Australian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers, much to the consternation of some of its members who could no longer lay claim to being the ‘Royal Corps’.

The Corps’ official abbreviation became ‘RAEME’ (and not RCAEME or CRAEME, as the Australian Army’s own rules on abbreviations would suggest) while the radio appointment title at all unit levels became ‘Bluebell’ in line with the British Army. It was a name that stuck: in general, the rest of the Army came to know all members of RAEME as ‘bluebells’, with unique descriptors evolving for the more specialized trades: mechanics are ‘spanners’ (with or without additional words of emphasis!); Recovery Mechanics are ‘recce mechs’; ‘gun plumbers’ for those that repair weapons; ‘sparkies’ for those with a knowledge of the mysteries of electricity, and so on.

But no matter what terms of reference or ‘endearment’ they are known by, the fact remains that they are there when needed, tool kit in one hand, replacement part in the other. Since the formation of the Corps in 1942, the Australian Army has not fielded a force overseas without its compliment of trades personnel, either attached to a unit of another Corps or as part of a Corps workshop unit.

The most substantial sustained overseas commitment since the end of the Second World War was to the war in Vietnam. Some idea of the numbers of RAEME personnel can be ascertained from the Australian Army Force Vietnam Order of Battle (OOB), though this only lists personnel in RAEME units, so must be taken as a minimum of the overall Corps commitment. The September 1965 OOB lists the ‘Detachment RAEME’ based at Bien Hoa with just 30 personnel. By June 1966, this had risen to 34 personnel in two workshops at Nui Dat (Detachment 131 Divisional Locating Battery Workshop and 1 Field Squadron Workshop), and 186 personnel at Vung Tau (17 Construction Squadron Workshop, 101 Field Workshop, and Detachment 1 Supply and Transport Workshop). By June 1968, with further increases in the size of the Australian Force, and more particularly, the diversity of its equipment, the numbers of RAEME had increased even further, with over 200 personnel based at Nui Dat and a similar number at Vung Tau, spread across several different workshops and Light Aid Detachments.

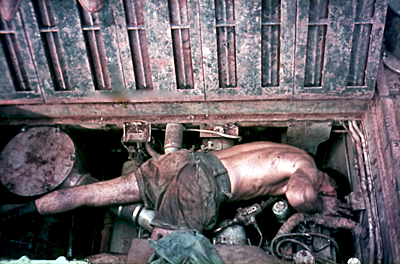

The complexity of equipment deployed to Vietnam had taken a significant leap in February 1968. The first Centurions landed at Vung Tau from the LSM Clive Steele in mid-February. Maintaining and repairing these ageing vehicles — the ‘youngest’, the Bridgelayer, was already five years old, while the ‘oldest’ was closer to 18 years of age — required sustained and often hazardous work in the tropical heat. True to the original definition of AEME being a ‘combatant’ arm, ‘bluebells’ were routinely ‘in the thick of it’ in support of their armoured Corps brethren, either crewing armoured recovery or repair vehicles as part of a sub-unit, or being deployed on forward repair tasks, often under fire. A tank and its crew, immobilized by a failed clutch or final drive, or having suffered mine damage to its suspension and tracks, depended on the ‘bluebells’ to get them back into the fight. On a number of occasions, the RAEME Armoured Recovery Vehicle crews retrieved damaged tanks during heavy contacts with the enemy.

The RAEME responsiveness to operational needs and the admiration this engenders is well illustrated by the recollections of Ian Farrant, a Centurion tank crew commander and Troop Leader in Vietnam. He recalled having an engine change carried out on his tank by 106 Field Workshop, but the new engine malfunctioned by the time they had traveled to their unit lines in Nui Dat. Farrant’s Troop was due to deploy on another operation in less than 36 hours, so time was extremely short: ‘We took it back to the workshop. They changed the engine over in 18 hours straight, using two crews, which meant we got to leave on time. Fantastic support!’.

The deployments that followed the Vietnam War — including Somalia, Rwanda, Cambodia, East Timor, the Solomon Islands, Bougainville, Iraq and Afghanistan — have all included an element of RAEME trades personnel to keep things working. Of the four armoured vehicles sent to Rwanda as part of the Australian Service Contingent to the United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR), three were M113A1 Armoured Personnel Carriers but the fourth was an M113A1 Fitters carrier, crewed by ‘bluebells’.

The RAEME maintenance element of the combat group in Southern Iraq was faced with similar challenges to their predecessors who had battled the sand and heat of the Middle East during the early stages of the Second World War. The answer was the same then as it is now: start work early – keep working late – and work during the heat of the day if you have to, but just get the job done.

The current commitment to Afghanistan is little different. Recovery mechanics crewing wreckers accompany convoys or retrieve immobilized vehicles, including too many that have been damaged by the enemy’s Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs). Bluebells from a wide variety of trade specialties maintain and repair everything from Australian Light Armoured Vehicles (ASLAVs) to X-ray machines, and just about every letter of the alphabet in between. The field conditions are still just as dangerous, the skills required just as technical, and the dedication just as evident as in every previous deployment.

Yet perusing the titles of the many, many books written about Australia’s wartime and warlike operations since the formation of the Corps during the Second World War, few record the day to day history of the Corps’ involvement at Unit level. There is Theo Barker’s ‘Craftsmen of the Australian Army: The Story of RAEME’ published in 1992, but precious few titles beyond that.

While the opportunity for recording first hand accounts of AEME veterans is fading quickly, there is still the opportunity to record the experiences of RAEME veterans and their exploits. This website goes a long way to preserving those memories, and providing valuable insight and education to those of us with little or no direct experience of the Army or the Corps of Royal Australian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers.